July in Christmas

The American marten (Martes americana) is often incorrectly referred to as a “pine marten” (Martes martes) when photographed in the U.S. Pine martens are a Eurasian species of marten not found in North America. Photo and Story by: Annalise Kaylor

It’s December. It’s almost a new year. I have winter wildlife photography on the brain.

I’m thinking about great grey owls perched on tamarack trees with their faces toward the ground, listening patiently, before crashing through the hardened top-crust of snow and capturing an unsuspecting vole on his grassy highway in the subnivean zone.

With the moose rut behind us, I’m thinking about the testosterone drops that this half-ton ungulate experiences with the changing daylight hours, hoping to get ahead of the change in time to photograph them in the snow and still with their antlers before they shed.

And then there’s the wolves. I grew up in wolf country, along the edge of the boreal forest in the upper Wisconsin northwoods. Summer camping trips meant falling asleep to a soundtrack filled with soothing wolf howls and the occasional staccato whippoorwill calls that filtered through. And yet, despite growing up in a place that has almost triple the number of wolves than Yellowstone National Park, it wasn’t until last year in Yellowstone that I saw my first gray wolf in the wild. The photograph I made was nothing more than a snapshot. I’d like the change that this winter.

As a working wildlife photographer, they are exactly what I should be thinking about. I’m in pre-production for our month-long visit to Wyoming to photograph wildlife in winter. But to put the “working” in “working wildlife photographer,” I need to also be thinking about July at Christmas.

Lead times for magazines and publications run three to six months ahead of our current season. Publishers and editors are well into prepping their spring issues for print at this time of year. Spring means migrating birds, baby animals, and all the creatures except any of the ones presently on my mind.

It’s easy enough for me to go through my archive and make sure all of my best stock work is uploaded and ready for sale. As written about before, the use of keywords and Smart Collections in Lightroom makes this seasonal review a task that takes me about 30 minutes. I’ve found a few images I hadn’t thought to put in Getty yet, so I take ten minutes to upload them. Done and done.

Not only is it the right time for publications to find them, but it’s also a nice amount of time to let these photos age for search optimization, get some attention, and then be ready to go when companies are looking for photos for their social media posts. Those tend to have a much shorter lead time, sometimes even same-day.

But how do I know what’s on the minds of the magazines I’d like to work with? This is one of my favorite strategies for identifying what I’m going to pitch, to whom, and when. And this article, I’m sharing one of my closely-held secrets with you: media kits.

Media kits have a couple of definitions these days. For example, “influencers” (ugh, anyone else as nauseated by that term as I am?) make them to show off their social media stats to companies they want to work with. But publishing companies make them to show off the power and audience they can deliver to potential advertisers.

The typical media kit for publishers has a WEALTH of information that we, as photographers, writers, and independent artists, can use to inform our pitches and time our submissions. And here, I’ll break down a few examples.

The first big piece of information is who their readers are. If you’re pitching a story, not only should you have read the publication a handful of times, but you should have solid reasoning as to WHY your story is relevant to their audience. And the media kit is a great way to learn, directly from the publisher, who their audience is. Publishing companies spend a lot of money dialing in these statistics. Take advantage of that.

Outdoor Photographer, which is part of a much bigger publishing company, Madavor Media, has one of the better examples of a media kit that I’ve seen. It’s extraordinarily thorough and well-designed, making it easy to find all of the information you need. With just this page, I know that despite nearly all of their audience having more than ten years of experience in photography, the primary motive of more than half their readers is to improve their photography skills. Their audience in print and online is dominated by male readers and a strong contingency of readers travel for their photography.

Immediately, I have some story ideas. Obviously, the first thing that comes to mind is pitching a piece on how professional, working photographers travel with their expensive wildlife photography gear. This is something both Jared and I talk about a fair amount - yes, we put our long lenses in the belly of the plane. Most photographers would never dream of checking their gear like that, but we do it every time we fly, even in other countries.

The thing every photographer loves to read about? Gear. We all love our gear, and one of us is always willing to help a fellow photographer out with reasons to justify buying more gear, “Yep, you can never go wrong with adding a *insert unnecessary new-fangled product you want here.”

Acknowledging the gear of another photographer while in the field is almost like a secret handshake in our world, “That the 600mm on that?” isn’t just a question, it’s a subtle cue that the inquiring mind has at least a modicum of photographic experience.

Looking at this page, I can see their entire year. Now this page is largely for advertisers to use, not photographers and writers. The timelines are for advertisers, for example, not for contributors. But advertisers want to make sure their product or service aligns with the topic of the issue. It’s an advantage to have a reader all hyped up after reading an article about a destination to then immediately see an ad about something offered in that destination. No-brainer, right?

The May issue looks like it might work for the hypothetical pitch in my head. It’s the travel issue, it’s a magazine for photographers who work outdoors like me, and it’s still five months out, which means there might still be time for me to squeeze into that issue, or perhaps an online-only piece. Digital timelines, as you can see in the calendar, are a little looser.

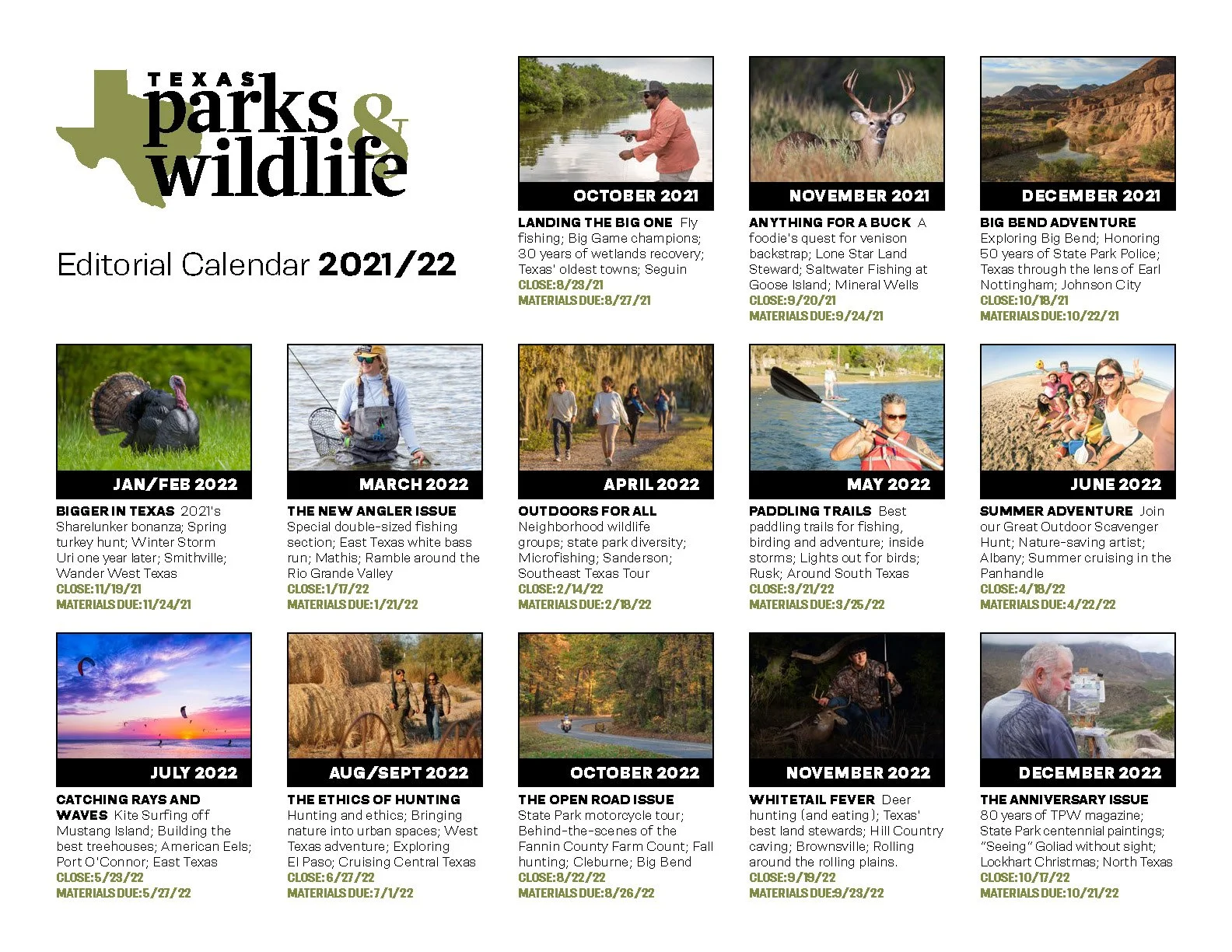

It’s not just the big publications that produce media kits. Regional and local publications put these out there, as well. This one from Texas Parks and Wildlife is a year old, but it illustrates what kind of work they are usually planning. And, this at least tells me what they WON’T be needed in the coming year. Publications rarely cover the same issue or theme back-to-back like that unless it’s a newsworthy update to a hot topic.

When I come across older calendars like this, I don’t sit around and then keep checking incessantly for updates. Rather, I grab the email of their advertising department and simply fire off an email asking if they’ve got their editorial calendar for the next year ready to go. If they do, they usually reply within 24 hours with a link or an attachment. Easy peasy. Pro tip: do this from an email address that isn’t your primary email (like a throwaway Gmail account) because advertising folks will bombard you with promotions.

Finally, I’d like to use this page from the 2022 media kit from National Wildlife Magazine to demonstrate a couple of other helpful pieces of information. First and foremost, they provide a lot more context around what features are planned for the year than many other magazines. This tells me they like a deep dive into a topic. Not surface-level information that anyone can Google in ten seconds. That makes sense because their audience is well-educated and academic. From the media kit, I learned that more of their readers have PhDs than a 4-year university diploma.

But the other piece of information I get here is a quick sample of their photography. Now, I’m already familiar with their style, but if you aren’t a subscriber or haven’t yet researched the publication, then this can be a good hint for you - if your work isn’t at this level, don’t submit. Don’t make a bad first impression. Also, you can see one of the photos is licensed via Alamy. This is another reason why both Jared and I advocate stock agencies. They’re competitive and saturated in many ways, but if you have unique photographs that stand out from the rest of the inventory, they will be found and they can help you fast-track your way into a great byline.

I still like to plan out my year in an analog fashion, so I am taking notes as I review editorial calendars. I like to keep a few ideas written in my field notebook, too, so I can refer to it for a gentle reminder I may have missed when planning a photo trip.

Then, it’s simply a matter of putting together a pitch or sending off an email to a photo editor to introduce myself and my work that I think might be a fit. Once I have an established relationship with an editor or have made it onto a photo needs list, I don’t really need to go back and review media kits time and time again. But as you’re building those relationships and really working to make strong connections, having this level of information and context truly makes you stand out from the crowd.